Scott Malcomson: Sovereign Virtues, Aziz Al-Azmeh and Michael Ignatieff on the Failures of Globalization

Article by Scott Malcomson, entitled "Soveign Virtues" brings together in a common framework, SFM Director Aziz Al-Azmeh and CEU Rector Michael Ignatieff.

Michael Ignatieff and Aziz Al-Azmeh, both born in 1947 and raised in the buzzing uplands of modernity’s post-Fascist reconstruction — one in Toronto, the other in Damascus — were of a generation that expected to make good on modernity’s second chance. If you think of the 19th century as globalization’s first round, and the nationalist and romantic reactions against it as taking up the period from late in that century through 1945, then the postwar period was supposed to be a wised-up reset. It could be guided by international developmentalism (often with a Marxist flavor) or liberal Western internationalism; in either case it would feature the spreading of the rule of law and global governance and the life-improving technologies of vaccination and birth control, electric washer and dryer, telephone and television, elevator and escalator, the automobile and the airplane.

And so it did continue, on through the Internet and the smartphone, and yet Ignatieff, Al-Azmeh, and their generation — and all of us — are also facing what looks less like a reset than a return of the repressed: a morbid, shape-shifting Islam and a revival of ethno-religious nationalism, both emphatically punctuated by violence and terror.

Striking from the Margins

Until recently, West and East seemed to be on divergent tracks. Both Ignatieff and Al-Azmeh now see them as coming together. Al-Azmeh identifies a pattern of “striking from the margins,” which is the title of a new project he is directing, with Carnegie Corporation of New York funding, at Central European University (CEU) in Budapest, Hungary. The margins can be political, economic, or spatial, and sometimes, as Al-Azmeh explained in an interview in Budapest, all three, as in Damascus’s “suburbs of misery.” What these margins have in common is that they provide recruits to social movements that are drawn to an unusual form of Islam. This is, Al-Azmeh stresses, not the Islam of their parents; rather it is an Islam refined by the Saudi Arabian movement called Wahhabism, a puritanical, ahistorical, and inherently apocalyptic Islam that acts as a stern counter to the realities of Muslim-majority countries. It is not a revival of Islam; it is a reconfiguration, one that constitutes “almost a new religion” that “is so alien as to require tremendous amounts of energy and violence in order to make itself stick.” While the Striking from the Margins project is focused on the Arab world and in particular on Iraq and Syria, Al-Azmeh sees parallels between the appeal of this reconfigured Islam and the appeal of ethno-religious nationalism to Westerners who believe they have been marginalized by globalization.

Ignatieff, who became rector of Central European University late last year, identifies the emergence of claims by citizens for state protection from the distant forces of globalization as a central geopolitical drama. Before joining CEU, Ignatieff had traveled the world — Los Angeles, Myanmar, Rio — as part of a Carnegie Centennial Project for the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. The project aimed, as he puts it in the resulting book, The Ordinary Virtues (September 2017), “to investigate what globalization has done to moral behavior in our time.” One of the project’s main findings, Ignatieff emphasized in a recent conversation at CEU, was that nation-states “are reasserting their sovereignty and trying to get the control that citizens want, enough control over the economy so you’ve got a job tomorrow, enough control over debts so you can pay your mortgage tomorrow. The basic stuff. And crucially, control against terrorism. Globalization has brought international terror, and it’s frightening people. People are turning back to the sovereign because it does what Hobbes said it would do, which is provide basic protection.”

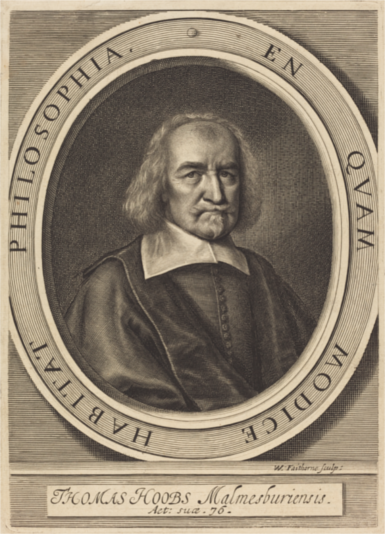

“People are turning back to the sovereign,” Michael Ignatieff says, “because it does what Hobbes said it would do, which is provide basic protection.” The English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) is best known for his defense of absolute sovereignty: the people agree to a social contract that transfers all of their rights to the Leviathan, which represents the abstract notion of the state. Engraved portrait of Hobbes by William Faithorne, after 1664. (Photo: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

This reconfiguration of the sovereign, under pressure from citizens marginalized by globalization, is not temporary. Nor, Ignatieff writes in The Ordinary Virtues, will globalization’s challenges be resolved by more globalization: “In this battle for control, the most powerful languages of resistance are not global but local: national pride, local tradition, religious vernacular.”

CEU is peculiarly well placed for examining such questions. The current government of Viktor Orbán, which has shaped post-Cold War Hungary and faces a weak and divided opposition, has encouraged a fear of Islam (although Hungary is notably lacking in actual Muslims). It insists on Hungary’s Christian identity and has pioneered a doctrine of “illiberal democracy” that embodies the return of the Hobbesian sovereign.

Central European University president Michael Ignatieff discusses how people are trying to find a balance between the benefits of a globalized society and the effects of globalization on their personal/national identities.

“Moral globalization is essentially not occurring,” Ignatieff said. “What’s occurring instead is ferocious national and local and regional defense of particularity — language, culture, religion, faith — against the forces of globalization.”

The Violent Failure of Modernism

Aziz Al-Azmeh’s considerable scholarly reputation is based on his insistence on multiplicity. His seminal book Islams and Modernities (1993) was built up from essays and lectures dating from the late 1980s. It was a time when Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) still sat at the center of the field, an irritant to some, a beacon to others; for everyone, unavoidable. Said’s donnish demolition of the Western edifice of the Muslim Orient reoriented the discipline. Islams and Modernities helped shape the post-Orientalism milieu, leaving Said’s anticolonial romanticism behind. While opposition to American militarism generally, and U.S. policy on Israel specifically, continued across generations, where Said would shake his fist at the English scholar W. Montgomery Watt or the American Bernard Lewis, Al-Azmeh was more apt to shake his at the Saudis, whose combining of oil money, a willingness to finance insurrectionaries in other people’s countries, and religious purism were eating away at the multiplicity of Muslim life in a way that Western Orientalism never could.

The multiple-Islams argument was solidly won in the academy, but proved of limited interest elsewhere, certainly in the West, which in the 1990s was meant to be gliding forward into a post-ideological, post-religious, post-modern future of globalist rationality.

And then things changed. Osama bin Laden was, Al-Azmeh says, “the perfect product of Wahhabi institutions, dropping only the element that constitutes a difference between jihadism and Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia, namely, the need to obey those in power.”

Between Orientalism and 9/11, Saudi Arabia had been refining and exporting a Wahhabi version of Islam that, once the West regained interest in Islam following the September attacks, was right there both to inspire the beset Muslim margins and give the West the monolithic Muslim enemy many seemed to need: “a total and totalizing culture which overrides the inconvenient complexity of economy, society and history . . . [an Islam] impermeable to all but its own unreason, utterly exotic, thoroughly exceptional, fully outside, frightfully different,” as Al-Azmeh put it in a post-9/11 addition to Islams and Modernities.

“This is not a revival of Islam but a reconfiguration. It is a very different perspective on things. In fact, these systemic changes are destructive of living traditions. They seek to substitute for them something which had once been very marginal. And to substitute it by force.”

— Aziz Al-Azmeh

As a Syrian and a Damascene, Al-Azmeh saw the rise of Wahhabism, and the concurrent decline of Arab modernism, in his own life. “If you talk of the Islamization of society,” he said as we spoke in his CEU office, “and I can tell you as a witness, we have seen a very visible difference in the lifetime of one generation, in the way in which religion is conceived, and the way in which people carry this religiosity, in which people announce their religion. Because religion had not previously been something that one announced. There had been a consensus — with the exception of some social and political margins — that religion is not really part of public life. This actually has changed. Religion had been isolated. It had been marginalized. But from this position of marginality it became, and this is a crucial term, a ‘stand-alone object.’ Once religion became a stand-alone object, it could be reconfigured as a social alternative.”

This reconfigured Islam, in essence Wahhabi Islam, became a rallying point and social alternative within Muslim societies themselves: “This is how Islamist ideologies appeared. What kind of an alternative is it? It requires a lot of violence, because this is quite an unusual form of rigorous piety, which had its origins in a part of the Arab world that for long had been marginal, specifically Saudi Arabia.”

Al-Azmeh is a compact man, carefully dressed, with an air that somehow blends impatience and amusement, his round baritone voice suited to an intense yet courtly manner that helps distance the violent failure of modernism that has stretched from his youth until now. Wahhabism, he says, was “looked at in the beginning with quite a lot of bemusement,” as Saudi clerics insisted that men had not actually landed on the moon and that in fact the sun did move around the earth. “Well into the 1930s and ’40s there were raids by the religious authorities on telegraph stations in Saudi Arabia, trying to grab the djinn, you know, these demons that were operating the system. This was really the object of much merrymaking, right? There is a very interesting speech by Abdel Nasser. You can find it on YouTube. The leader of the Muslim Brotherhood suggested to Nasser that he should impose the veil on Egyptian women. Nasser replied, ‘First of all, sir, your daughter is a medical student and she does not cover her head. If you can’t keep your house in order, how am I to keep all Egypt in order? And secondly, who am I to impose the hijab on Egyptian women?’ The audience thought it was hilarious. It was a subject of hilarity. Do look it up on YouTube.”*

Michael Ignatieff on how Islam is in a battle for its own soul as varying groups vie to set themselves as the official spokesmen for the religion.

But Wahhabism had money, conviction, and, it now appears, time on its side. Gradually, this stand-alone Islam from the Arabian peninsula approached the center and Nasser began to look quaint. “This is not a revival of Islam but a reconfiguration,” Al-Azmeh observes. “It is a very different perspective on things. In fact, these systemic changes are destructive of living traditions. They seek to substitute for them something which had once been very marginal. And to substitute it by force.”

Al-Azmeh has seen this happen in his native Syria and sees something similar happening in his adopted Europe, where he has taught for most of his career. He noted that in the 1950s Muslim hardliners in the Wahhabi mode received very few votes in Syria. “But then you find, as in Europe, that the parties with programs of social transformation, communists and so forth, are now the natural constituency of the extreme right here and the Islamists where I come from. The dynamics are similar. The Trump victory also involved what was once marginal coming to the center. Much of the talk of the rise of the extreme right in Europe has also involved moving from the margins to the center, as the center is no longer able to hold its hegemony over the rest of society.”

From Prison House to Creative Destruction

It is safe to say that Michael Ignatieff never set out to be a student of religion. His earliest work was on the Scottish Enlightenment, exploring in particular how Adam Smith and his generation in Edinburgh understood the morality of a market-based global economy. He studied at Oxford with the liberal philosopher Isaiah Berlin and embarked on a life of teaching and writing. Berlin was, however, a keen observer and historian of European nationalism, and a man of the world, and when ethnic nationalism surged in Europe immediately following the decline of Soviet Communism, his student Ignatieff went to see what was happening. He became a reporter, not least in Blood and Belonging: Journeys into the New Nationalism (1993), which focused mainly on the Balkans. Ignatieff went on to combine journalism with more scholarly reflections; he wrote moral-political essays, somewhat in the Berlin mode (The Needs of Strangers, 1994), but often with a debater’s urgency, and preoccupied specifically with human rights (Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry, 2011). He published three novels. He even entered politics, a sincere misadventure which he bookended, of course, with books: True Patriot Love: Four Generations in Search of Canada (2009) followed by Fire and Ashes: Success and Failure in Politics (2013).

A woman walks past a colorful mural at the Oinofyta refugee camp, in Evvoia, Greece. As of March 2017, the camp was home to some 550 Afghan refugees, many of whom have been stuck there, under harsh conditions, after the closing of the borders. (Photo: Ayhan Mehmet/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

“I’ve been on a continuous journey, from the end of the Cold War in ’89, to understand how nations and communities maintain their identities and their cohesions in the storm of creative destruction we call globalization,” Ignatieff said in his Budapest office. “First it was the post-’89 context, in which an empire disintegrates and nations that have been in the prison house of the Soviet system then set out to create new national identities. And so democracy comes to those places as a desire for ethnic majority rule; and when it becomes ethnic majority rule, then what do you do about the minorities? Very quickly that led to wars, majority-minority wars, and 20 years on we’re still struggling to create a stable state order.”

Ignatieff identifies the most important moral change or our time — the empowerment of billions of people around the world to believe that their voice matters — and details the conditions that fostered this change.

For the Ordinary Virtues project, Ignatieff returned to Bosnia. He found that “it’s a frozen conflict, still unable to resolve the problems that defined it in the ’90s and nearly tore it apart. The new project tries to widen out the frame and ask: What’s happened to human rights? Because human rights, in many ways, was the driving ideology of the post-’89 era if you were a liberal internationalist like myself, or you were a cosmopolitan like myself. It was the idea that the right solution to this majority-minority thing was to protect minorities with human rights and create new political orders in which human rights would limit and control the competition between majority and minority. That way you’d have a kind of peace, you’d have stable social orders. Well, we now look at international human rights and it’s in big trouble.”

“It is simply false to say that the United States is a Christian country or that France is a Christian country. The Christian tradition is crucial in both countries, but these are now secular republics founded by constitutional orders that very deliberately and self-consciously put religion in its place.”

— Michael Ignatieff

In the course of his travels for the Ordinary Virtues project, Ignatieff came to see human rights as being a bit like English: a global language that works best when it is localized, accepting that in this process it is no longer universal, and indeed that one local human-rights dialect, like local English, might not even be comprehensible somewhere else.

Human rights has also lost its great patron, the United States, “a country that since 1945 liked globalization because it thought it would dominate it, but has now got huge currents in domestic American politics saying: Protect us from it. That’s a real change. And it has ripple effects across the globe. Because if the United States is not a confident entrepreneur of globalization it will also not be a confident entrepreneur of human rights. . . . Human rights was a vehicle for transnational and transborder moral scrutiny. And that’s being pushed back everywhere.”

Demonstrators supporting Central European University (CEU) are blocked by police officers in Budapest on April 9, 2017, near the headquarters of Fidesz, the party that has governed Hungary since 2010. The Fidesz government, led by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, had just passed a law that could force the closure of CEU. Rallies in Hungary and elsewhere in Europe have continued as CEU, led by Rector Michael Ignatieff, negotiates with the government over the university’s future. (Photo: Attila Kisbenedek/AFP/Getty Image)

This twin disenchantment leaves states to turn in on themselves. But are the means even available for satisfying the economic demands of citizens marginalized by globalization? “We’re all in this balancing thing,” Ignatieff said, “of trying to have globalization without being destroyed by it, and defending identities while having the benefits of being able to join a global society. And nobody’s got a solution here.”

Getting Religion

The surge in a particular type of identity politics in Europe might provide solace but it is hard to see how it could provide resolution. One of the more aching paradoxes of this identity politics is that it increasingly involves religion, which as Ignatieff pointed out once produced “some of the most powerful agents of moral globalization.” Now European countries that once defined themselves as secular are getting religion. In 2016 French presidential candidate François Fillon released a book called Vaincre le totalitarisme islamique (Defeating Islamic Totalitarianism) while this year France’s former Europe minister Pierre Lellouche equates Islam with Nazism in Une guerre sans fin (War Without End).

“Suddenly,” Ignatieff said, “European societies that have been secular, and trying to push back the religious identity at the core of European identities, are suddenly reinventing themselves, reinventing their identities as Christian, faced with what they see as a Muslim threat. This seems a catastrophe to me. Not because Christian culture and Christian themes and Christian resonances aren’t central to European culture and aren’t a structuring element of our deepest moral beliefs and always will be. I don’t believe in the thesis of secularization; religion is going to be here forever, to give people belonging, meaning, and guidance. But it is simply false to say that the United States is a Christian country or that France is a Christian country. The Christian tradition is crucial in both countries, but these are now secular republics founded by constitutional orders that very deliberately and self-consciously put religion in its place. And they do so not from lack of respect for religion, but out of fear that when religion controls the public sphere the result is intolerance, savagery, and war. And Europe has a lot of experience with that.”

Michael Ignatieff describes how the resurgence of protectionism and anti-free trade is being driven more by concerns for identity rather than economics.

Islamists and the European right are, in Aziz Al-Azmeh’s view, “two alternatives of polity” that are becoming twins. They are both “replacing civility with identity, replacing citizenship with identity based on blood or religious identification.” Islamist Wahhabism, it can be argued, had very little to do with Europe or the West, but its effects — “I think we are landed with this for a generation,” Al-Azmeh said — might well include a reconfiguration of Christianity, which of all the possible scenarios for modernity must qualify as the least expected. And yet we have certain European leaders and an American president apparently convinced that their nations are Christian enough to justify making religious distinctions among who will be allowed in, and who won’t. This would constitute a Wahhabi victory of sorts, even as the West’s intentions might be entirely the opposite.